The Christian Bible is comprised of many different literary forms such as letters, stories, parables, and prophesies. This sacred text not only provides a foundation for shared beliefs and practices, it also provides a shared history that shapes Christian beliefs, worship, culture, and identity. This lesson will address the composition of the Bible, significant elements in the Bible, and the role of the Bible in Christianity.

Objectives

- describe the composition of the Bible

- recognize significant stories, events and teachings in the Bible

- interpret the messages and meanings communicated in the Bible

The Christian Bible

A Christian Bible is a collection of books regarded as divinely inspired. Most versions consist of an Old Testament and a New Testament, and some versions include a separate section, called an apocrypha, between the old and new testaments. Significant versions of the Christian Bible in English include the Douay-Rheims Bible, the Authorized King James Version, the English Revised Version, the American Standard Version, the Revised Standard Version, the New American Standard Version, the New King James Version, the New International Version, and the English Standard Version.

Old Testament

The Old Testament is the first part of most Christian Bibles, it is based primarily upon the Hebrew Bible (or Tanakh). The books that comprise the Old Testament canon, as well as their order and names, differ within Christian denominations. The Catholic canon comprises 46 books, and the canons of the Eastern Orthodox and Oriental Orthodox Churches comprise up to 49 books. The most common Protestant canon comprises 39 books. The books in common to all the Christian canons correspond to the 24 books of the Tanakh, with some differences of order, and there are some differences in text. Additional numbers reflects the splitting of several texts (Kings, Samuel and Chronicles, Ezra–Nehemiah and the minor prophets) into separate books in Christian bibles.

The books that are part of a Christian Old Testament but are not part of the Hebrew canon are sometimes described as deuterocanonical. In general, Protestant Bibles do not include the deuterocanonical books in their canon, but some versions of Anglican and Lutheran bibles place the books in a separate section called Apocrypha. These extra books are ultimately derived from the earlier Greek Septuagint collection of the Hebrew scriptures and are also Jewish in origin. Some are also contained in the Dead Sea Scrolls.

The Old Testament consists of many distinct books by various authors produced over a period of centuries. Christians traditionally divide the Old Testament into four sections: (1) the first five books or Pentateuch (Torah); (2) the history books telling the history of the Israelites, from their conquest of Canaan to their defeat and exile in Babylon; (3) the poetic and “Wisdom books” dealing, in various forms, with questions of good and evil in the world; and (4) the books of the biblical prophets, warning of the consequences of turning away from God.

The New Testament

The New Testament is a collection of 27 books discussing the teachings and life of Jesus, as well as events in first-century Christianity. It is a collection of Christian texts originally written in the Koine Greek language, at different times by various different authors. The 27-book canon of the New Testament has been almost universally recognized within Christianity since at least Late Antiquity. In almost all Christian traditions today, the New Testament consists of the four canonical gospels (Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John), the Acts of the Apostles, the fourteen epistles (letters) of Paul, the seven catholic epistles, and the Book of Revelation.

The earliest known complete list of the 27 books of the New Testament is found in a letter written by a 4th-century bishop in Alexandria in 367. It was first formally canonized, or recognized, during the councils of Hippo (393) and Carthage (397) in North Africa. These councils also provided the canon of the Old Testament, which included the apocryphal books. There is no scholarly consensus on the date of composition of the latest New Testament texts. Some scholars date all the books of the New Testament before 70 AD, while most scholars date some books much later than this.

Gospels

Gospel literally means ‘good news’, but in the 2nd century it came to be used for the books in which the Christian messages were delivered. Most scholars believe that the four canonical gospels, (Matthew, Mark, Luke and John) were written between AD 66 and 110,and built on older source. Each gospel contributes its own distinctive, and sometimes conflicting, understanding of Jesus and his divine role. All four are anonymous and acquired modern names in the 2nd century. It is almost certain that none of the accounts were written by an eyewitness. regardless, they are the main source of information on the life, teachings, activities, death and resurrection of Jesus.

Synoptic Gospels: Mark, Matthew and Luke

Mark, Matthew and Luke are considered synoptic Gospels because they share overlapping themes, words and phrases. The three books share similar sayings, parables, and events which lead scholars to believe that all three draw from a single source. The source is referred to as Q (from Quelle, German for ‘source’). Although they were named after three followers of Jesus, the actual authors are unknown. Scholars believe they were not written to account for the details of Jesus’ life, but to inform future generations of believers.

The Gospel of Mark

The Gospel of Mark is considered the earliest gospel written approximately 30 years after Jesus’ death and presumably during the decade preceding the destruction of Jerusalem in 70 CE. Yet it is positioned second after Matthew. It is attributed to St. Mark the Evangelist (Acts 12:12; 15:37), an associate of St. Paul and a disciple of St. Peter, whose teachings the Gospel may reflect. It is the shortest of the four Gospels, and most scholars agree that it was used to compose Mark and Luke; more than 90 percent of the content of Mark’s Gospel appears in Matthew’s and more than 50 percent in the Gospel of Luke. Although the text lacks literary polish, it is simple and direct, and, as the earliest Gospel, it is the primary source of information about the ministry of Jesus.

The Gospel of Matthew

The Gospel of Matthew is the first of the four Gospels. It has traditionally been attributed to St. Matthew the Evangelist, one of the 12 Apostles, described in the text as a tax collector (10:3). The Gospel According to Matthew was composed in Greek, probably sometime after 70 CE, with evident dependence on the earlier Mark. There has, however, been extended discussion about the possibility of an earlier version in Aramaic. Numerous textual indications point to an author who was a Jewish Christian writing for Christians of similar background. The Gospel According to Matthew consequently emphasizes Christ’s fulfillment of Old Testament (Tanakh) prophecies (5:17) and his role as a new lawgiver whose divine mission was confirmed by repeated miracles.

The Gospel of Luke

The Gospel of Luke is the third of the Gospels. It is traditionally credited to St. Luke, “the beloved physician” (Col. 4:14), a close associate of the St. Paul the Apostle. Luke’s Gospel is clearly written for Gentile, non-Jewish, converts: it traces Christ’s genealogy, for example, back to Adam, the “father” of the human race rather than to Abraham, the father of the Jewish people. The date and place of composition are uncertain, but many date the Gospel to 63–70 CE, others somewhat later.

Despite its similarities to the other Synoptic Gospels, however, Luke’s narrative contains much that is unique. It gives details of Jesus’ infancy found in no other Gospel: the census of Caesar Augustus, the journey to Bethlehem, Jesus’ birth, the adoration of the shepherds, Jesus’ circumcision, the words of Simeon, and Jesus at age 12 in the temple talking with the doctors of the law. It also is the only Gospel to give an account of the Ascension, the ascent of Christ into heaven on the fortieth day after the Resurrection. Among the notable parables found only in Luke’s Gospel are those of the good Samaritan and the prodigal son.

John

The Gospel of John is the fourth gospel, and it is the only one of the four not considered among the Synoptic Gospels. Although the Gospel is ostensibly written by St. John the Apostle, “the beloved disciple” of Jesus, there has been considerable discussion of the actual identity of the author. The language of the Gospel and its well-developed theology suggest that the author may have lived later than John and based his writing on John’s teachings and testimonies. The writing style and message in the Gospel of John differs from the synoptic gospels in that it is more of a theological narrative regarding Jesus’ identity as a messiah and savior. Several episodes in the life of Jesus are recounted out of sequence with the synoptics, and the final chapter appears to be a later addition. The Gospel’s place and date of composition are also uncertain; many scholars suggest that it was written in Asia Minor, about 100 CE for the purpose of communicating about Christ to Christians of Hellenistic background.

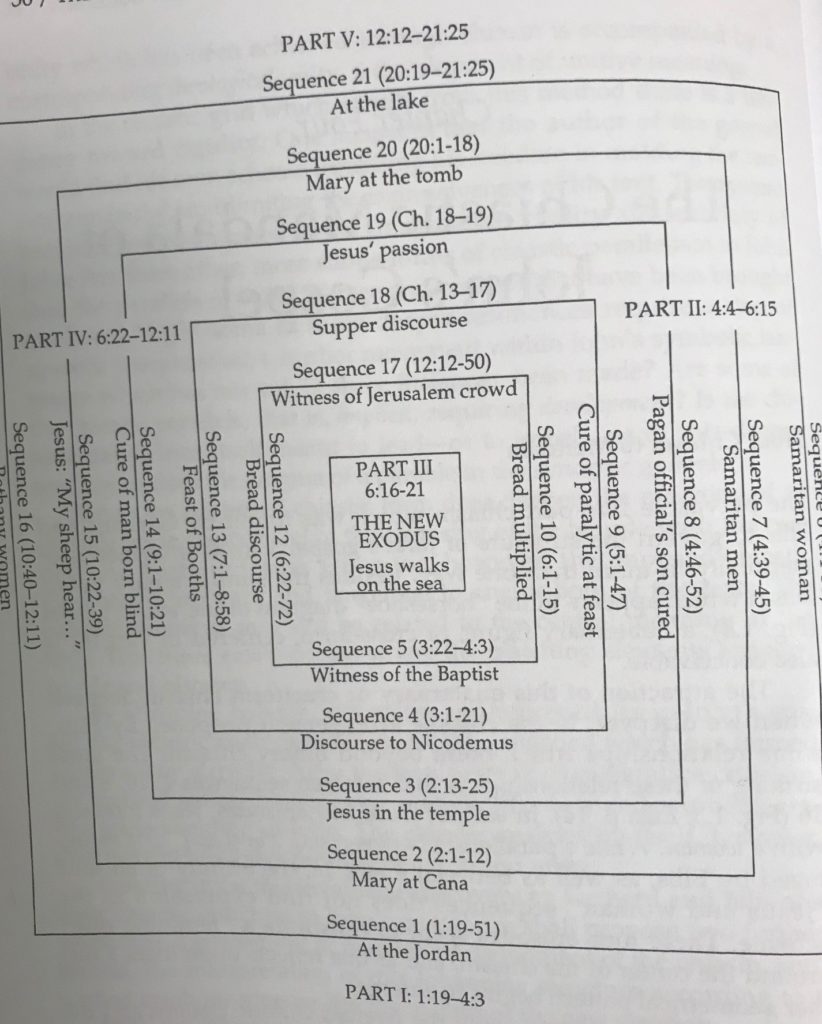

The structural organization of John also reflects literary styles in Eastern traditions. Scholars such as Bruno Barnhart claim that John offers a mystical roadmap organized around a single truth: that God poured divine reality into humankind through the person of Jesus Christ, and this is centered Jesus walking on water. This belief stands at the center of the gospel, and every episode in the narrative is arranged around that core affirmation and event. The gospel, when interpreted this way, assumes a mandalic pattern in which all parts are related to the center and through it to each other through symbolic significance, chiastic textures, and patterned, repetitive relationships between narrative episodes.

Gnostic Gospels – The Nag Hammadi Library

The Nag Hammadi Library is a collection of thirteen ancient books, or codices, containing over fifty texts. It was discovered in Egypt in 1945. The collection is important because it includes a large number of primary Gnostic Gospels, texts thought to have been destroyed during the early Christian struggle to define orthodoxy. It includes scriptures such as the Gospel of Thomas, the Gospel of Philip, and the Gospel of Truth. The translation of the Nag Hammadi library was completed in the 1970’s, and it prompted a re-evaluation of early Christian history.

To learn more, read an excerpt from Elaine Pagels’ excellent popular introduction to the Nag Hammadi texts, The Gnostic Gospels and watch the full-length BBC documentary below.

Acts of the Apostles

The Acts of the Apostles, also known as Acts, is the fifth book of the New Testament, and it provides a history of the early Christian church. Acts was written in Greek, presumably by the Evangelist Luke, whose gospel concludes where Acts begins, namely, with Jesus’s Ascension into heaven. Acts was apparently written in Rome, perhaps between AD 70 and 90, though some think a slightly earlier date is also possible. After an introductory account of the descent of the Holy Spirit on the Apostles at Pentecost (interpreted as the birth of the church), Luke pursues as a central theme the spread of Christianity to the Gentile world under the guiding inspiration of the Holy Spirit. He also describes the church’s gradual drawing away from Jewish traditions. The missionary journeys of Paul are given a prominent place, because this close associate of Luke was the preeminent Apostle to the Gentiles. Without Acts, a picture of the primitive church would be impossible to reconstruct; with it, the New Testament letters of Paul are far more intelligible. Acts concludes rather abruptly after Paul has successfully preached the gospel in Rome, then the acknowledged center of the Gentile world.

The Pauline Epistles

a significant portion of the New Testament is comprised of a series of letters to various Christian communities written by the Apostle Paul who, unlike the Apostles, never met Jesus in person. Formerly known as Saul of Tarsus, Paul was a Greek-speaking Jewish man born around the same time as Jesus in the area of modern-day Turkey. He spent his early adult life as a Pharisee persecuting Christians until he experienced a vision prompting his conversion to Christianity. Paul describes his conversion experience in his letters: Galatians (1:16) God revealed his Son to him, 1 Corinthians (9:1) he saw the Lord and The Book of Acts describes a bright light. Paul interpreted this vision as a testament that God had indeed chosen Jesus to be the promised messiah. Three years later, he went to Jerusalem to meet the leading Apostles at the time; Peter, James and John. After the meeting he began a twenty year career missionizing to gentiles, or non-Jews outside of Jerusalem (Galatians 1:16).

Paul and his companions traveled by ship and walked, probably beside a donkey carrying tools, clothes, and perhaps scrolls. His letters state they were often hungry, ill-prepared, and cold (Philippians 4:11–12; 2 Corinthians 11:27), and many times they had to rely on the charity of their converts. Despite the hardships, Paul established several Gentile churches in Asia Minor and at least three in Europe.

Before Paul, Christianity was primarily viewed as a message for the Jewish people. Paul’s gentile-based mission was more successful than the Jerusalem-based missions of the other apostles, and today Paul is considered the most influential Apostle. His letters written in Koine, or common Greek, are considered sacred scripture and the word of God by most Christians. His teachings vary from those of other Apostles in that Paul’s interpretations seldom drew from Jewish law, and he frequently conflicted with the other apostles. For example, a “circumcision faction” of the Jerusalem apostles (Galatians 2:12–13), argued that converts should undergo circumcision as a sign of accepting the covenant between God and Abraham. They later preached directly to the Gentile converts both in Antioch (Galatians 2:12) and Galatia and insisted they be circumcised. This led to some of the strongest invectives in Paul’s letters (Galatians 1:7–9; 3:1; 5:2–12; 6:12–13). In time, Gentiles were forbidden to adopt markers of Jewish identity.

In the late 50s BCE, Paul returned to Jerusalem and was arrested for taking a Gentile too far into the Temple precincts. After a series of trials, he was sent to Rome where it is believed he was executed by the executed possibly as part of the mass execution of Christians ordered by the Roman emperor Nero who blamed Christians for the great fire in the city in 64 CE.

However, scholars believe that not all Epistles called Pauline were written by Paul. Early letters such as Romans, I and II Corinthians, Galations, Philippians, I Thessalonians, and Philemon indicate that Paul believed that the end of the world was imminent. Yet Ephesians, Colossians, II Thessalonians, and the Pastorals (I and II timothy and Titus) emphasize the Church and appear to be written for future generations of believers by followers of Paul.

Catholic Epistles

The Catholic Epistles are distinct from the Pauline by their more general contents and the absence of personal and local references. They represent different, though essentially harmonious, types of doctrine and Christian life. The individuality of James, Peter, and John stand out very prominently in these brief remains of their correspondence. They do not enter into theological discussions like those of Paul, the learned Rabbi, and give simpler statements of truth, but protest against the rising ascetic and Antinomian errors, as Paul does in the Colossians and Pastoral Epistles. Each has a distinct character and purpose.

Book of Revelation

The Book of Revelation, often called the Revelation to John, the Apocalypse of John, The Revelation, or simply Revelation, the Revelation of Jesus Christ, or the Apocalypse, is the final book of the New Testament and therefore the final book of the Christian Bible. Its title is derived from the first word of the text, written in Koine Greek: apokalypsis, meaning “unveiling” or “revelation”. It is the only apocalyptic document in the New Testament canon (although there are short apocalyptic passages in various places in the Gospels and the Epistles). The author names himself in the text as “John”, but his precise identity remains a point of academic debate. The bulk of traditional sources date the book to the reign of the Roman emperor Domitian (AD 81–96).

The book spans three literary genres: the epistolary (letters), the apocalyptic, and the prophetic. It begins with John, on the island of Patmos in the Aegean Sea, addressing a letter to the “Seven Churches of Asia”. He then describes a series of prophetic visions, including figures such as a Seven Headed Dragon, The Serpent and the Beast, which culminate in the Second Coming of Jesus. The obscure and extravagant imagery has led to a wide variety of Christian interpretations: symbolic interpretations consider that Revelation does not refer to actual people or events, but is an allegory of the spiritual path and the ongoing struggle between good and evil.

Apocrypha

The Apocrypha generally consists of 14 booklets of which 1 and 2 Maccabees and 1 Esdras are the main documents and form the bulk of the apocryphal writings. First Maccabees is an historical account of the struggle of the Maccabee family and their followers for Jewish independence from 167 to 134 BC. Second Maccabees covers the same ground but dramatizes the accounts and makes moral and doctrinal observations. Other books are Tobit, Judith, Baruch, Ecclesiasticus, and The Wisdom of Solomon. Since neither Jesus nor the apostles make any reference to the apocryphal books, most Christians have regarded their authority as secondary to that of the 39 books of the Old Testament.

Interpreting Messages and Meanings in the Bible

This lesson addressed the composition of the Christian Bible, significant elements in the Bible, and the role of the Bible in Christianity. The ancient text not only documents the life and teachings of Jesus and the history of the early church, literature within the Bible also provides a framework for contemporary Christian beliefs, practices, and everyday living. Although globalization and diaspora have contributed to the diversification of distinctly different Christian communities throughout history and around the world, the Bible is the text that binds Christian people together.

References and Resources

For discussion: Select one of the educational videos from The Bible Project presenting a story or ritual in the New Testament and research one additional scholarly article about the story or ritual. Using the theoretical frameworks presented in the Introductory module in this course, interpret the messages and meanings conveyed by the story or ritual you selected. Post the video in discussion with your interpretation using the format below;

- Introduction: Introduce the ritual or story (not the video) and make a declarative thesis statement using a specific theoretical perspective (Be sure to cite where the ritual or story is located in the Bible.)

- Body: Interpret the ritual or story – what are the messages and meanings? What role does it play and why?

- Conclusion: Tie your thesis back to what was presented in the body.

- References: Cite the additional article in a proper format

(min 500 words) Be prepared to discuss the story, law or ritual in class.

When you complete the discussion, move on to the Global Christianity lesson.