Since prehistoric times, symbolism has been pervasive throughout all forms of religious belief and practice; scripture, mythology, storytelling, teachings, and art. From 25,000 year old cave paintings to televised sermons today, humans have used symbols and representations to communicate spiritual and religious thoughts and feelings in ways that words fail to deliver. To develop a better understanding of the role of symbols and meanings in religious expression and practice, this lesson will examine the different types of symbols and representations used in world religion, explore patterns in religious symbolism through history and across cultures, and introduce different strategies and techniques for interpreting religious symbols.

Lesson Objectives

- define symbolism and representation

- describe the role of symbols and representation in religion

- recognize common symbolic meanings through different mediums in world religions

- interpret how symbols and meanings express unique ideas and experiences in world religions

Symbolism

Humans have a unique capacity to communicate meanings through representation, the process of producing a symbol to communicate an idea or set of ideas. Humans create symbols to signify ideas by assigning meanings to arbitrary representations. What this means is that the symbol itself does not possess an inherent quality or trait associated with the meaning it represents; the meaning has been assigned to the symbol. Since meanings are assigned to a symbol, the same symbol can represent different meanings between groups and individuals according to different interpretations, histories, and experiences.

Symbolism can strengthen religious messages and meanings, make complex concepts easier to understand, and add emotion and feeling in a way that words and language fail to fulfill. Symbol-making using objects (plants, animals, elements, etc.), colors, sounds, time (day, night, seasons, etc.), and scenarios (stories, myths, etc.) have been used to represent messages and meanings intended to establish an aura or mood that is not captured through simple literal translation or words. Therefore, religious symbolism can provide a window to the heart, mind and soul of a believer, and can help others develop deeper understandings of the meanings and experiences that shape a religion.

Religious Symbols & Icons

Religious symbolism often contains highly complex meanings that reflect centuries of accumulated knowledge and tradition. All major historical religions have made some use of religious images and icons, also referred to as votive images, although the use of icons has been very controversial, especially in the Abrahamic group. Unlike arbitrary symbols, an icon is a sign that represents a message or meaning by virtue of a resemblance such as an image of Jesus or Mohammed. For many believers, the icon’s virtue of resemblance conflicts with the Abrahamic requirement for monotheism, worship of only one deity. Iconoclasm is a belief in the need to destroy religious icons for religious or political reasons. Iconoclasts are people who engage in or support iconoclasm.

The TedEd video below presents the history of art in world religions and the role of iconography and the iconoclasm throughout several centuries.

Iconoclastic movements attest to the power and significance of symbols and symbol-making in religious thought and practice. This makes it important in religious studies to investigate how unique and shared symbols are used by religious groups and individuals. While some symbols are distinctively unique to a particular religion, other symbols are shared by a wide variety of cultures and religions through different times and geographies.

Archetypes & the Collective Consciousness in Religion

In his book, Images and Symbols (1991) Mircea Eliade shows that myth and symbol were a mode of thought that came long before logical reasoning and remains an essential function of human consciousness. He describes and analyzes some of the most powerful and pervasive symbols across many cultures and religions through history.

Reoccurring symbols, or archetypes, are universal representations that have been used in different times and cultures. Archetypes include the Great Mother, the Wise Old Man, the Shadow, the Tower, Water, the Tree of Life, the Golden Rule, and many more. Scholarly debate surround the origins of archetypes; are they coincidental or are they tied to a collective consciousness among all people? The Collective Conscience is a term coined by 20th century psychoanalyst, Carl Jung, to refer to structures of the unconscious mind which are shared among beings of the same species. According to Jung, the human collective unconscious is populated by an interaction between primitive instinct and by archetypes that are shared through subconscious connections. Archetypes are considered universal by Jung because they are repetitive through history and across cultures, and Jung argues that they must therefore emerge from a collective consciousness that connects humans through a shared human psyche. Jung argued that the collective unconscious influenced individuals who live out universal symbols and meanings through personal experiences. The psychotherapeutic practice of Jungian psychology revolves around examining a person’s relationship to the collective unconscious. This includes the interpretation of dreams among other things. Jungian theorists also believe that we can develop a deeper understanding of societies and civilizations by examining archetypical myths, stories and legends that communicate the unique perspectives of a culture while reinforcing that cultures connectivity to the universal human experience.

Archetypes in Mythology

A myth is a story consisting of events that are ostensibly historical and explaining the origins of a cultural practice or a natural phenomenon. Myths may be a sacred story that communicates religious or spiritual significance for those who share it; a traditional narrative passed down through generations that communicates life lessons or a cultures systems of thought and values; a tale about divinity; or an explanation as to why something (ie suffering) exists. Myths oftentimes involve symbols with multiple meanings as well as archetypical beings such as gods and goddesses, heroes and heroines, or particular animals and plants. Monomyths are archetypical myths that repeat throughout history and across cultures such as creation stories that narrate how the world or a people came into existence. The video below covers theories of myth, the different ways mythology has been studied, and different ways to interpret interpret myth academically.

An American mythological researcher, Joseph Campbell, wrote a famous book entitled, The Power of Myth, which illuminates the significant role of myths and mythology in humanity. His subsequent book, The Hero with a Thousand Faces, identified common patterns running through hero myths and stories throughout histories and across cultures. Through comparative analysis, Campbell outlined several basic stages included in nearly every hero-quest mythology which he refers to as “The Hero’s Journey.” these stages are also evident in a wide variety of religious stories in world religion scriptures that depicting the struggles and triumphs of individuals.

The TedEd video below describes the archtypical stages in the Heroe’s Journey.

Symbols in Scripture and Storytelling

Symbolic interpretation of religious scripture has a very long history. In the case of Christianity, for example, Bruno Barnhart (1989) points out that symbolic interpretation was the dominant mode of religious study for the first thousand years of Christian history. He argues that symbolism in the biblical narrative has a deeper level of significance beyond the literal meaning.

A parable is a short story that typically ends with a moral lesson. Parables rely on symbolism, similie, and metaphor to communicate a complex lesson in a succinct narrative. Parables are often used in religious texts such as the Upanishad, the Torah, the Bible, and the Quran.

In the second chapter of the Quran, (Al Baqra 2: 259) for example, there is a story of a man who begins to doubt the ability of God to resurrect as he passes through a place where people died. Subsequently, God caused him to die, and then resurrected him after a hundred years. When God asked the man how long he slept, he replied only a day because the food he brought with him was still fresh. The man’s donkey, on the other hand, became a skeleton. God joined the bones, muscles, flesh and blood of the donkey brought it back to life. This Islamic parable aims to teach a moral lesson in three ways: God has control over all things and time; God has power over life, death, resurrection and no other can have this power; and humans have no power, and they should put their faith only in God.

Parables are great teaching tools to convey complicated moral and philosophical lessons in a way that is relatable and understandable to the reader’s personal experiences. Parables take common scenarios in day-to-day lives and use them to represent deeper meanings and messages. They are effective because the reader is guided to draw a conclusion and then apply the lesson’s principles in life. There are a wide range of other forms of symbolic represention in the Humanities, and we will take a closer look in future lessons. Now, we will examine the meanings and effects of symbolic representation of the body, particularly in terms if gender and race, within the Humanities.

Gender and Religious Symbolism

The status of women in religious society is also reflected through visual art, literature and storytelling. In her book, The Serpent and the Goddess, Mary Condren analyzes how the declining status of women in ancient Ireland during Christianization parallels changes in the mythology of Brigid. The pre-eminent Goddess in early Irish religious traditions was considered the patroness of poetry, smithing, medicine, arts and crafts, cattle and other livestock, sacred wells, and serpents. Yet her role in mythology changes over time, from a woman of immense power to a victim of rape. Her decline, and that of women, is epitomized in Saint Patrick’s eradication of serpents from Ireland which is celebrated every year during St. Patrick’s Day. The story of Lilith in Judaism has also changed throughout history. The video below describes the Lilith story, and for more information on the Lilith story, visit Jewish Women’s Archives.

The dynamic and changing nature of symbols and symbol-making in religious history makes it important to situate religious symbols within their unique social and historical contexts. This not only helps us develop a better understanding of the symbols themselves, but it also sheds light on the historical and social changes that have taken place within religious communities through time and across cultures.

Symbolism through Ritual and Performance

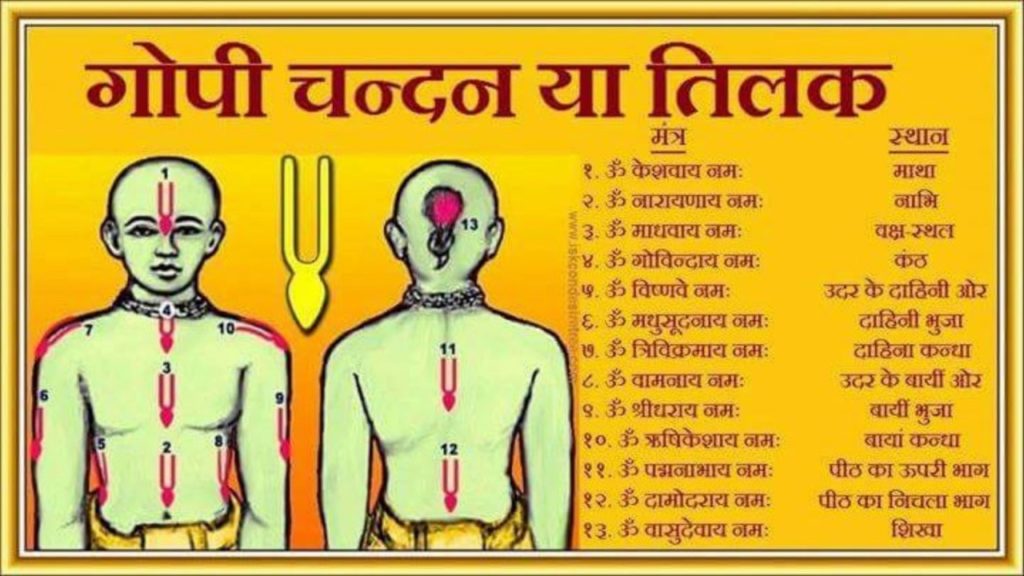

Religious symbolism also includes performances such as rituals and ceremonies that express meanings, enhance emotion, communicate ideas and reinforce beliefs.

Rituals are oftentimes rooted in stories and can be tied to ancient practices. Common rituals include activities during worship, weddings and funerals, holidays, affirmation of faith, conversion to a religion, preparing and sharing meals and sacrifice. rituals may be strictly prescriptive with specific actions taking place in a very precise manner at a particular time or they can be spontaneous and improvised. Rituals may be performed as a group or by individuals.

The Aeon video below depicts different rituals from daily mundane activities to religious activities among five five years olds in five different religions.

Five from The Mercadantes on Vimeo.

Symbols, Identity and Power

Religious symbols can also communicate identity and belonging to a religious community. Adornment such as clothing, jewelry, hair styles, and body modification (circumcision) can represent an individual’s inclusion to a religious community and their participation in specific beliefs and practices. Symbolism can also help members of the same community identify one another in a mixed society. Bumper stickers, t-shirts, tattoos, and social media memes help community members express beliefs while at the same time connecting with others who share them.

Religious symbolism can also expresses power and domination over a religious community. A top European Union court was criticized for religious oppression after it ruled that employers can ban visible religious symbols by employees, such as Islamic headscarves. (To read the article, click here.) Religious symbolism called ‘holocaust badges’ was also used by the Nazi party in Germany during the mid-twentieth century to identify and exterminate Jewish people during the holocaust. For more information on holocaust symbolism on badges, click here.

Appropriation of Religious Symbols

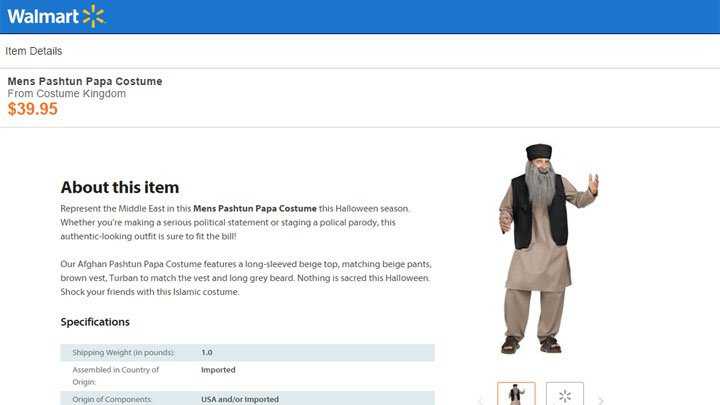

Religious appropriation, or misappropriation, occurs when a person or group takes something culturally or religiously significant from another group in order to perform, modify, or adopt for their own personal, private, or commercial purposes. Misappropriation is controversial because the people who appropriate the symbolism oftentimes fail to honor and respect the meanings and significance of the religious symbol. It is particularly problematic when members of a dominant culture appropriate symbolism from a dis-empowered group. While the appropriation of Islamic culture with the ‘Pashtun Papa Costume’ sold by Walmart in 2014 shocked Americans and prompted Walmart to apologize, less blatant religious appropriations are pervasive such as the commercial use of yoga, yin/yang signs, Ohm signs, and other religious symbols used by people outside the religious community.

Interpreting Religious Meaning & Experience through Symbolism

Religious symbols provide a window into the beliefs and practices of a religious community, and they also reflect the unique social and historical experiences that connect people to each other as well as to ancient practices. This is why it is important to not only learn about and identify the many different uses and modes for symbol-making, it is just as significant to be able to situate symbols within their specific context. This lesson provided a brief definition of symbolism and representation, described the role of symbols and representation in religion, presented common symbolic meanings through different mediums, and demonstrated how symbols express unique ideas and experiences in world religions. Information from this lesson will be applied to following lessons as we explore Judaism, Christianity, Islam, Hinduism and Buddhism.

Readings & Resources

- Baer, Hans A. (1998). William H. Swatos Jr (ed.). “Symbols”, in Encyclopedia of Religion and Society.

Your Score:

Your Ranking:

Writing Assignment: Provide a 500-word synopsis of a scholarly article addressing archetypes, a re-occurring symbol, in one or more of the world religions addressed in this course. Post your synopsis in the discussion forum and respond to at least two other student posts comparing and contrasting the articles.

Follow the steps below:

- Login to the Tyree Library using your ID (See Research Tools module in Canvas for assistance.)

- Go to Google Scholar, Jstor or any other academic database and type in key words such ‘archetypes religion’ or ‘archetypes Islam’ etc.

- Download and read the article (logging into the library will provide access to more articles.)

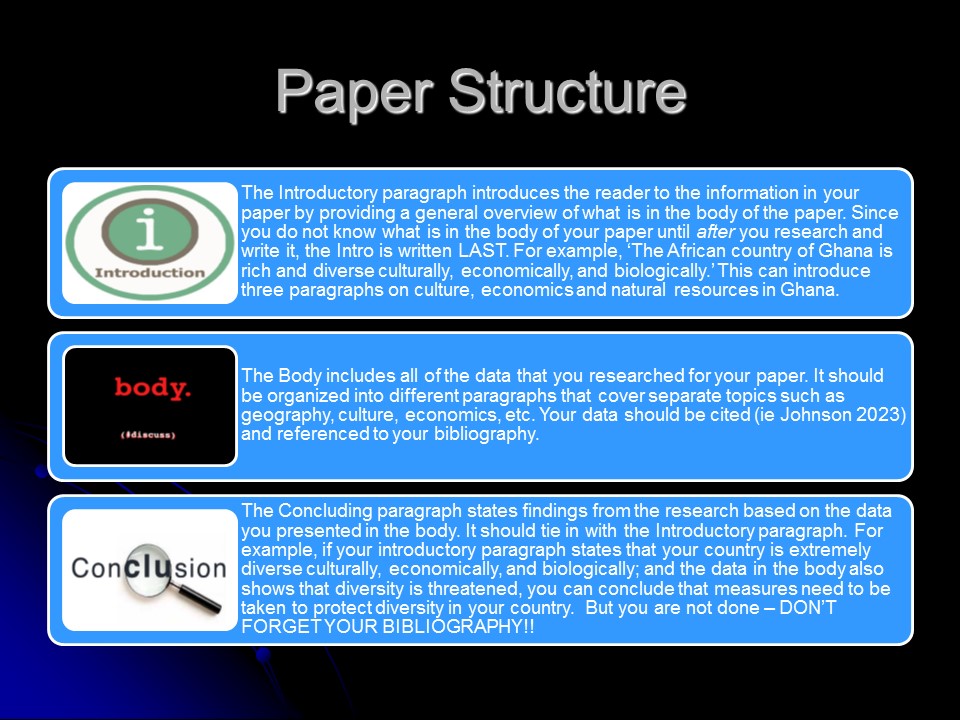

- Write your synopsis in ‘Intro – Body – Conclusion – References’ format: Introductory paragraph introduces three points in or about the article, Body consists of three paragraphs each addressing one of the points stated in the introduction, and the Conclusion reiterates the introduction in more detail. Cite the article in a formatted reference at the end (See Research Tools module in Canvas for formatting assistance.)

When you complete the writing assignment, prepare to take the Introductory module quiz in Canvas.