What does it mean when we say someone is telling the truth? Is there just one truth, or can there be many truths? Is it possible for two people to make contradictory statements while both are telling the truth? Does believing something make it true? How do we differentiate between truths and falsehoods and who gets to decide? This lesson will touch on different approaches to truth, truth-making and perspective.

Lesson Objectives

- recognize the relationship between (T)ruth and systems of power

- identify the role of perspective and its implications for truth-making

- describe different philosophical approaches to truth and perspective

- formulate a position on truth and perspective using terms and concepts from the lesson

Truth & Power

‘What is truth?’ asked a jesting Pontius Pilate in in the Christian Book of John more than 2,000 years ago. Pilate did not stay for an answer. Yet today, various theories and views of truth continue to be debated among scholars, philosophers, and theologians. For example, the old adage “history is written by victors”, reflects the relationship between winners and the right to write stories about the past. We can assume that if the British won the American Revolutionary War or if Germany won World War II that the histories we read about those events would have been written very differently and this would affect our understanding of the past.

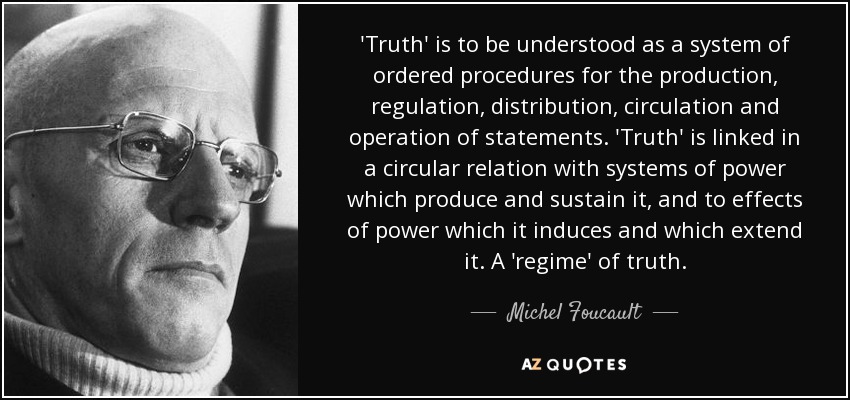

An important element in the conversation about truth is the relationship between truth-making and systems of power. Truthmaker theorists state that for a proposition to be made true is for it to be true in virtue of the existence of some entity, which is called its “truthmaker.” Michel Foucault, a 20th century French philosopher, shaped modern understandings of power by moving attention toward the role of truth-making within systems of power (ie law, education, religion, family, etc.). In his book, ‘Power is Everywhere,’ Foucault argues that systems of power shape our social and cultural systems, frame the way we view the world, are embedded in the words and language that we use, and has penetrated every aspect of our lives in a way that cultivates our idea of reality and truth through what he calls ‘regimes of truth’ (Foucault 1991; Rabinow 1991.)

Foucault defines regimes of truth as historically specific mechanisms that produce ideas that function as true in particular times and places. This approach defines truth as an event which happens in history rather than something that is discovered or revealed. Truth happens through various techniques, and these techniques occur within regimes of truth that are controlled by power.

- the types of communication that a society uses to function as true

- the mechanisms that one uses to distinguish true from false

- the procedures that are sanctioned for obtaining truth

- the status of those who are charged with saying what counts as true

Using Foucault’s line of reasoning, for example, we can analyze how a society evaluates the truthfulness of the statement, “I am not the child’s parent.”

- identify the types of communication that establishes the nature of a parent-child relationship (ie scientific, social, legal, political, etc.)

- identify any mechanisms in place to distinguish what is and is not parentage (ie family structures, fostering arrangements, biological associations) and how are those mechanisms granted authority (ie state legal structures, religious doctrines, scientific testing, etc.),

- determine the procedures used to test the statement (ie DNA analysis, testimony, history of relations with the child, amount of time spent together, etc.),

- recognize the status of those who have established the criteria (1 through 3) laid out so far (such as judges, scientists, religious leaders, chiefs, intellectuals, etc.) and the structures that grant them status over others (ie politics, scriptures, universities, etc.)

According to Foucault, 1-4 is “a system of ordered procedures for the production, regulation, distribution, circulation and functioning of statements.” Each society has its own regimes of truth which it accepts as a function of truth-making. This is why Foucault presents truth as an historical event that takes place rather than an absolute entity that can be revealed.

of a circular relationship between

power and truth/knowledge.

The historical events that create truth, however, do not occur in an objective and independent manner. According to Foucault, truth is linked to what he refers to as the politics of truth, “ a circular relation with systems of power which produce it and sustain it, and to effects of power which it induces and which redirect it.” Within the politics of truth, power is expressed in a society through the acceptance of knowledge, which he defines as a society’s understanding of truth. In the circular system, power creates institutions that control subjects (people who support power.) This enables power to produce truth/knowledge, and the truth/knowledge reinforces the systems of power. Foucault argues that “truth isn’t outside power, or deprived of power.” On the contrary, truth is created by power, truth and power justify each other, and truth maintains the power that creates it.

Watch the documentary trailer, The Social Delimma (2020), below and consider the ways that the social media regime operates as a power structure that shapes and defines truth for its users. (If you are on social media, it is a good idea to watch this documentary so you can become more aware of the ways the media platforms are engineered to manipulate and profit from its users.)

Foucault’s work attacks the very notion of truth. In Madness and Civilization (1961) Foucault challenges the notion of insanity by investigating the historical relationship between power structures and the asylum as an instrument of power. In The Archaeology of Knowledge (1969) Foucault interrogates the history of power and the production of ideas to present knowledge, the archive of what we know, as a product of historical events. In The Order of Things (1966) Foucault outlines the historical construction of the sciences, and The Birth of Biopolitics (1978) shines light on the political function of the intellectual (scholars) and higher education.

Foucault aimed to deconstruct what we think we know by interrogating how we have come to know what we know. He was a strong force in the Post-Modernist philosophical approach which aims to critically examined theories and ideas presented as fact, truth, objective, absolute and/or real. Yet, if what we think, know, feel, and believe is nothing more than a product of history and systems of power, will we ever be able to determine what is true? Or is our reality nothing more than a matter of perspective?

Perspective

Perspective is a point of view relative to positioning. Perspectivist theory is usually taken to mean that a person’s perspective is shaped by their social positioning and the associations created through the personal experiences of the individual, which is known as their lens.

There are many different philosophical approaches to perspectivism, yet many of them rely on three main ideas:

- Our knowledge of the world is inevitably shaped by our particular perspectives.

- Any one of these perspectives is as good as any other.

- Any claims to objective or authoritative knowledge are consequently without ground.

Many schools of philosophy attribute perspectivism to German philosopher, Friedrich Neitzsche, who critiqued past philosophers for largely ignoring the influence of their own perspectives on their work. He argued that they had failed to account for their own perspectival effects within their philosophies. Nietzsche referred to perspective as “optics of knowledge,” and he rejected the idea that knowledge involves a form of objectivity to reveal the way things really are.

Well before Neitzsche, Zhuang Zhou, commonly known as Zhuangzi, was an influential Chinese philosopher who lived around the 4th century BC. Zhuangzi’s perspectivism rests on his argument that one’s linguistic and conceptual perspective determines what one claims to know. He presents perspectivism as a ‘way of knowing.’ To learn more about Zhuangzi, watch the video below.

Perspectivism is also illustrated in story of the The Blind Men and the Elephant, a famous Indian parable that describes how six blind sojourners encounter an elephant in their life journeys. Blindness represents human limitations in the capacity to see from all perspectives. The elephant represents truth. Each blind man in the parable draws a different and very conflicting conclusion about the nature of the elephant according to their relative position around the elephant. The video below is a poetic adaptation of the parable:

The Blind Men and the Elephant parable is used today to highlight the problem with ideas about absolute truth or exclusive religious claims. By recognizing the limitations of a single point of view, it aims to encourage us to consider the perspectives of those who are different from us while validating and legitimizing the perspectives of those who are disempowered and therefore left out of the construction of “truth”.

Relativism, Truth and Morality

Relativism is the idea that ideas are relative to the differences in perception and consideration, and because of this, there is no universal or objective truth. There are many different forms of relativism. Truth Relativism is a doctrine that there are no absolute truths. Moral Relativism challenges moral facts and principles related to “right” and “wrong”. Cultural Relativism is the principle of regarding beliefs, values, and practices of a culture from the viewpoint of that culture itself. Originating in the work of anthropologist, Franz Boas, in the early 20th century, cultural relativism influenced research in the social sciences such as Anthropology and Sociology as a means to avoid judging another culture by the standards of one’s own culture, a practice referred to as ethnocentrism.

Moral and Cultural relativism are addressed in the field of metaethics. To learn more about metaethics, watch the Crash Course Philosophy video below.

Critiques of Foucault, Post-modernism and Relativism

Post-Modern and Relativist perspectives have received considerable criticism, particularly in the context of human rights and social justice. Modernists, such as Noam Chomsky, argue that relativism undermines the notion of human rights which is based on a universal acceptance of certain aspects of right and wrong, and in doing so relativism inadvertently excuses atrocities such as genocide, slavery, child sex abuse, and more. As the video above explains, from a relativist perspective, the Nazi party was right … from the cultural point of view of a Nazi. This theoretical battle plays out today in the controversy surrounding female genital mutilation (FGM) which is also referred to as female circumcision, depending on one’s relative point of view.

FGM is a traditional practice that has been carried out for many generations primarily in North Africa and the Middle East. The globalization of Women’s Right’s Movements originating in Europe and the United States has generated a worldwide campaign to end the practice. Watch the Global Citizen video to learn more.

Activist groups such as Global Citizen argue that FGM is a violation of human rights. Yet, a very strong and vocal group of women support the practice as a cultural right. Cultural relativists argue that female genital circumcision in some cultures is no different than the cultural practice of male genital circumcision in the U.S. and Europe. The global anti-FGM movement, from a cultural relativist point of view, is an expression of ideological domination by European and American systems of global power. To hear this critique by a group of Kenyan women, listen to the PRI podcast below.

After considering both sides, what do you think?

In the context of the Blind Men and the Elephant, however, modernists argue that while each blind man has a limited perspective on the elephant (truth), that does not mean that the elephant (truth) does not exist. Rights are considered truths that are self-evident. (What defines a ‘right’, however, is another philosophical rabbit hole best addressed in a philosophy class.) The goal of modernism is to collectively learn about the elephant/truth in its totality; and this requires sharing our experiences, perspectives and points of view.

Nonetheless, the philosophical battles between modernists and post-modernists has raged on for decades since the legendary philosophical shootout between Noam Chomsky and Michel Foucault in the 1970s. Their conversation touches on the topics of relativism, human nature, and power. If this is your thing, watch the famous hour-long debate in the video below.

Truth and Social Justice

Despite philosophical differences on truth, perspective, and relativism, both modernists and post-modernists concern themselves with the notion of obtaining justice through a critique of the power systems the create injustice and undermine human rights. James Baldwin, a prominent Civil Rights-era intellectual and novelist, believed that telling the truth can deeply unsettle our assumptions about ourselves and our relations to others. He also argued that the concept of truth could play a concrete role in social justice. James Baldwin’s approach to truth and racial justice resurged during the Black Lives Matter Movement. To learn more about James Baldwin’s work and its implications for racial justice, listen to the Philosophy Talk Podcast here.

Speaking Truth to Power

‘Speaking Truth to Power ‘ is a phrase often used by political dissidents that refers to a non-violent tactic against the knowledge, histories, and/or propaganda produced by systems of power. The concept dates as far as classical Greece, with the term parrhesia to refer to ‘free speech.’ The idea behind speaking truth to power is that it is based on the initiative to break the monopoly of knowledge by power through the imposition of present a different set of ‘facts.’ Speaking truth to power includes but is not limited to; political protest, bearing witness, and writing an alternative account of an event. However, Noam Chomsky is dismissive of “speaking truth to power” tactics. He argues that “power knows the truth already, and is busy concealing it”. It is the oppressed who need to hear the truth, not the oppressors. Yet Baldwin’s notion of ‘white innocence’ counters Chomsky by arguing that oppressors are often deluded into believing they are right and are often ignorant to their role in oppressive regimes and the perspectives of the oppressed.

Truth with a capital T

‘Truth with a capital T’ refers to the truths created by those who are in power. Capitalizing the ‘t’ in truth makes it a pronoun, a name for a particular type of truth. For Postmodernists, since there is no universal Truth (capital “T”), there are only “truths” (small “t”) that are particular to a society or group of people and limited to individual perception. Written or verbal statements can reflect only a particular localized culture or individual point of view. A well-worn catchphrase we hear in this regard is, “That may be true for you, but not for me.”

Truth and Reconciliation

A truth commission or truth and reconciliation commission is a commission tasked with discovering and revealing past wrongdoing in the hope of resolving conflict left over from the past. Truth commissions are, under various names, occasionally set up by communities emerging from periods of internal unrest, civil war, extreme inequality, genocide, and/or dictatorship.

Truth and reconciliation is an integral part of the Restorative Justice approach that aims to reconcile the conflict between a victim and an offender. The goal is for each to share their experience of what happened, to discuss who was harmed by the crime and how, and to create a consensus for what the offender can do to repair the harm from the offense. The process begins with the offender offering ‘truth’ by taking responsibility for their actions and acknowledging the harm they have caused in order to have the opportunity to redeem themselves. Restorative Justice ranges a wide variety of activities from the legal intervention programs at the River Phoenix Center for Peacebuilding in Gainesville, Florida to the Fambul Tok community healing program in post-civil war Sierra Leone. To learn about Fambul Tok, watch the video below.

A wide variety of community-based truth and reconciliation events such as Deliberate Dialogues in the Southern United States aim to illuminate the racial injustice and atrocities of slavery, Jim Crow and widespread lynchings of African Americans that were covered up and denied by racist regimes of truth.

Truth, Perspective and the Humanities

The Humanities provide a platform for people to learn and share unique ideas, perspectives, and experiences from a collective point of view that has accumulated throughout history and across cultures. Philosophy not only provides a framework to contemplate and question ideas and concepts, it also enables people to interrogate the source of ideas and concepts, such as truth, that are widely taken for granted. Each piece of art, a lyric in a song, a line in a poem, representation in art, or a new philosophical idea represents a different facet of the elephant of humanity which speaks a different truth about the human experience. Studying the Humanities takes us closer to exploring the totality of what it means to be human.

Questions to Consider:

- According to Michel Foucault, what is the relationship between truth and power?

- What is perspectivist theory; what two philosophers have contributed to our understanding of perspective?

- What is relativism, cultural relativism and moral relativism?

- What is Noam Chomsky’s response to Foucault and the problem of relativism with human rights?

- What is the role of truth in social justice?

References and Resources:

- Newell, Paul (2005) Truth: Philosophy for Beginners. The Galilean.

- Griffith, Aaron. 2019. Truthmaking. Oxford Bibliographies

- Pluralist Theories of Truth, Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy

- Foucault: Power is Everywhere (1992)

- Foucault (1976) Biopolitics

- Connolly, T. Perspectivism as a Way of Knowing in the Zhuangzi . Dao

- Critiquing cultural Relativism, Jaret Kanarek (2013)

- Jones, B. (1966). James Baldwin: The Struggle for Identity. The British Journal of Sociology,17(2), 107-121.