African culture is considered one of the most influential cultural forces in the United States and throughout many parts of the Americas. This is particularly the case in the southern U.S. where a high concentration of enslaved African people and their descendants reshaped the cultural landscape with the integration of African food, music, religion, language, stories, and craftwork into the American social fabric. Despite the significance of African culture in the Americas, it remains one of the most looked over cultures in the US. This lesson will provide a very brief introduction of African cultural survivals in the United States.

Lesson Objectives

- describe the history of African culture and people in early U.S. history

- recognize the influences and contributions of African culture and people in mainstream American culture

- evaluate an African cultural survival in Florida

African Influences in Early American Culture

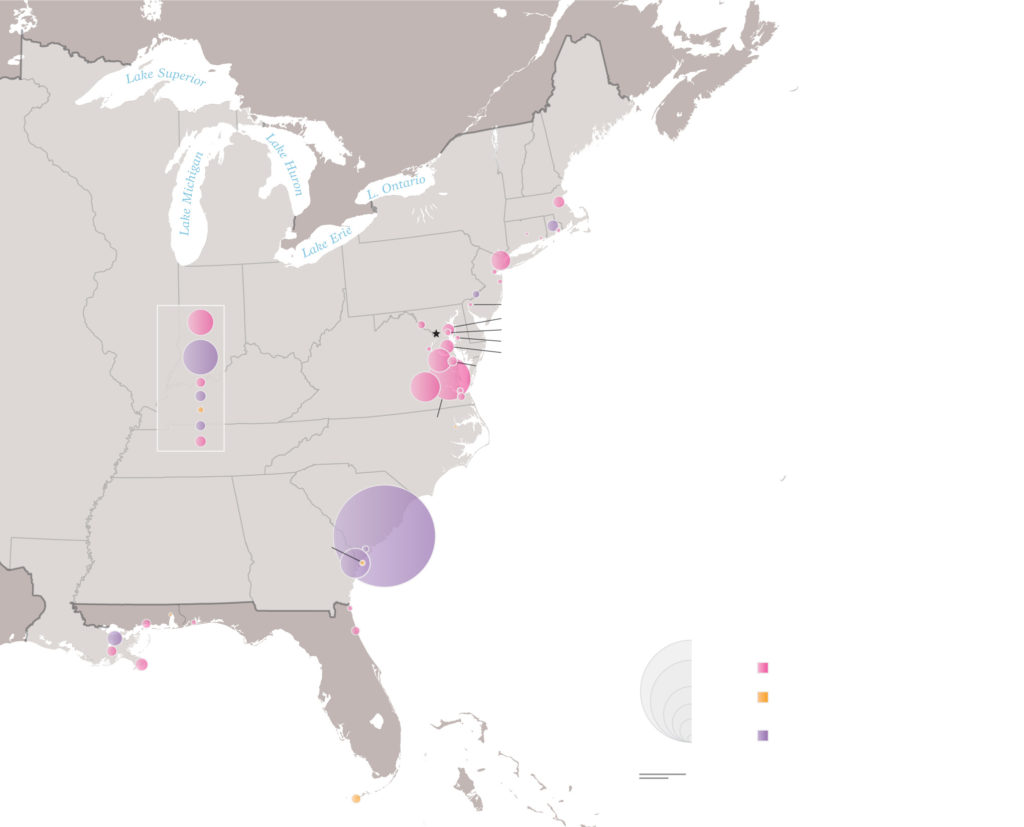

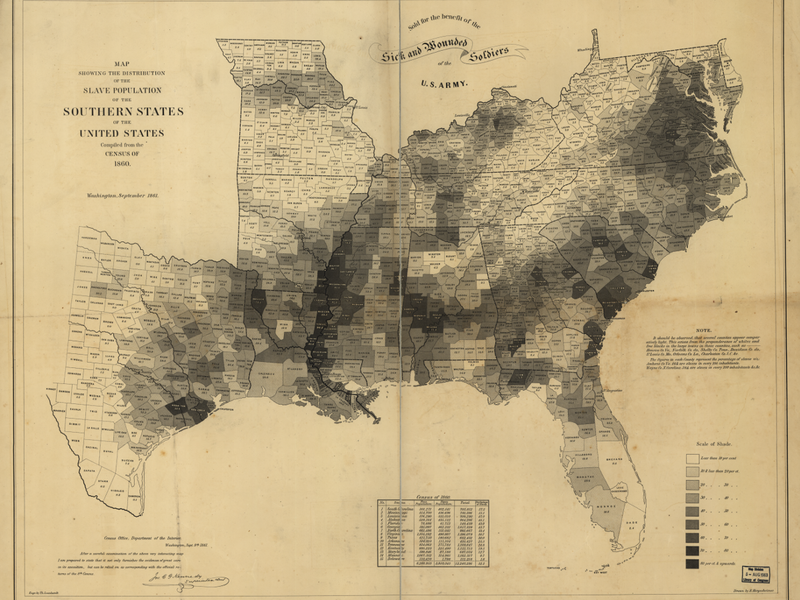

Enslaved people in the antebellum South constituted about one-third of the southern population in the United States. Though it is impossible to give accurate figures, some historians have estimated that 6 to 7 million enslaved African people were imported to the New World during the 18th century alone. Most lived on large plantations or small farms. By the time President Lincoln signed the Emancipation Proclamation on January 1, 1863, more than three million enslaved people lived in what would become the Confederate States. For nearly two centuries the American cultural landscape was shaped by millions of enslaved African people and their descendants. Despite oppressive abuses and regulations that prohibited enslaved Africans and African-Americans from engaging in cultural practices such as speaking African languages, worshipping African religions, and maintaining traditional family and kinship ties, African cultural survivals spread and adapted to new circumstances on American soil.

Herskovits and The Myth of the Negro Past

Before the twentieth century, few academics explored the role of African culture in American culture, and apart from a small group of African-American scholars, most social researchers represented African-American culture as a failed attempt to copy European culture. In 1928, Melville Herskovits, a Jewish-American anthropologist, challenged widely held assumptions about black people in America. His books The American Negro and the The Myth of the Negro Past (1941) redefined the ways that mainstream anthropologists analyzed African-American culture. He argued that black culture in America was “not pathological” as white anthropologists had previously represented, he instead tied black culture to African culture. His work traced regional traditions in art, music, dance, and other expressions to the cultural persistence of African traditions in spite of generations enduring enslavement and racial discrimination. In the years immediately following Herskovits’s death, a wide range of civil rights activists, including The Black Panther Party, used The Myth of the Negro Past to reclaim African culturalisms and black identity in America. The film Herskovits at the Heart of Blackness presents the contributions of Melville Herskovits’ work and addresses the politics of who has the right to define someone else’s identity, and what it means when the people being defined are excluded from the conversation.

While Herskovits helped mainstream African-American studies in the United States by connecting African culture and African-American cultures, globalization studies has also shown that African culture has also shaped mainstream American culture in terms of religion, food, music, crafts, literature, and other elements in the American cultural fabric.

African Words in the English Language

American English, or Englishes, is distinctly different from British forms of English because it includes the integration of an immense number of words, phrases and meanings contributed by immigrants and enslaved people speaking other languages. As a result, American English and particularly Southern forms of English spoken by people of African and European descent includes a broad spectrum of words, phrases and meanings that are African in origin. The chart below includes a short list of examples.

| Banana; fruit | from Wolof via Spanish or Portuguese | |

| Banjo; a type of stringed instrument | probably Bantu mbanza | Etymonline |

| Bongo; a type of hand drum | West African boungu | Etymonline |

| Buckaroo; from buckra – “white man or person” | from Efik and Ibibio mbakara | Mason, Julian (1960). “The Etymology of ‘Buckaroo'”. American Speech. 35 (1): 51–55. doi:10.2307/453613. JSTOR 453613 |

| Chigger; a type of insect | possibly Wolof or Yoruba jiga “insect” | Etymonline |

| Chimpanzee; a type of primate | Bantu language, possibly Kivili ci-mpenzi. | American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language, Fifth Edition, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company, 2011 |

| Cola; a type of drink | Temne kola, Mandinka kolo | Etymonline |

| Djembe; a type of hand drum | from West African languages | |

| Ebony | from Ancient Egyptian hebeni | Etymonline |

| Fan; an enthusiast | from Yoruba “fani mọ́ra” meaning “to attract people to you” | |

| Gnu; small watercraft | from Khoisan !nu through Khoikhoi i-ngu and Dutch gnoe | |

| Goober; peanut | possibly from Bantu (Kikongo and Kimbundu nguba) | |

| Gumbo; a type of cuisine | from Bantu (Kimbundu ngombo meaning “okra”, with similar roots in Tshiluba, Umbundu and other Bantu languages from the Angola/Congo region) | |

| Jazz; a type of music | possibly from West African languages (Mandinka jasi, Temne yas), though many possible etymologies have been proposed, including the English jasm and French jaser | |

| Jenga; a type of puzzle game | Swahili word for “build” | |

| Jive; a type of dance | possibly from Wolof jev | |

| Juke, Jukebox; coin-operated player for records | possibly from Wolof and Bambara dzug through Gullah Gullah juke bawdy (as in juke house brothel) | The Collins Dictionary |

| Jumbo; very large | from Swahili (jambo “hello” or from Kongo nzamba “elephant”) Gullah jamba, elephant; of Afr orig.: reinforced by P. T. Barnum’s use of it for his famous elephant, Jumbo | The Collins Dictionary |

| Mojo; power or magic | from Fula moco’o “medicine man” through Louisiana Creole French or Gullah | |

| Mumbo Jumbo; bewilderment | from Mandingo name Maamajombo, a masked dancer | |

| Okra; a type of vegetable | from Igbo ókùrù | |

| Safari; an excursion | from Swahili travel, ultimately from Arabic | |

| Shea; A tree and the oil Shea butter which comes from its seeds, | comes from its name in Bambara | |

| Tango; a type of dance | probably from Ibibio tamgu | |

| Tilapia; a type of fish | possibly a latinization “tlhapi”, the Tswana word for “fish” | Aquatic Community Database |

| Tote; carrying bag | West African via Gullah | |

| Yam; a type of edible root | West African (Fula nyami, Twi anyinam) | |

| Zombie; walking dead | likely from West African (compare Kikongo zumbi “fetish”, Kimbundu nzumbi “ghost”), but alternatively derived from Spanish sombra “shade, ghost” 1871, of West African origin (compare Kikongo zumbi “fetish;” Kimbundu nzambi “god”), originally the name of a snake god, later with meaning “reanimated corpse” in voodoo. But perhaps also from Louisiana creole word meaning “phantom, ghost,” from Spanish sombra “shade, ghost.” Sense “slow-witted person” is recorded from 1936. | |

Ebonics, also called African American Vernacular English (AAVE), formerly Black English Vernacular (BEV), dialect of American English spoken by a large proportion of African Americans. Many scholars hold that Ebonics, like several English creoles, developed from contacts between nonstandard varieties of colonial English and African languages. Its exact origins continue to be debated, however, as do the relative influences of the languages involved. Ebonics is not as extensively modified as most English creoles, and it remains in several ways similar to current nonstandard dialects spoken by white Americans, especially American Southern English. It has therefore been identified by some creolists as a semi-creole (a term that remains controversial).

Ebonics or AAVE is often defined as “The language and discourse patterns of African slave descendants in the United States, which reflect the survival of African languages in the English used by these descendants” (Smitherman 2015: 547). This hypothesis argues that AAL developed from a creole language that arose out of early contact between Africans and Europeans, with this creole variety being widespread in the antebellum South. One supporting fact is that this creole variety wasn’t just specific to the mainland American South, showing similarities to other well-known English-based creoles, such Gullah and creoles found in Jamaica and Barbados. In fact, Gullah remains an important case, as Gullah may have traces of the creole that gave rise to AAL even today. Another interesting piece of supporting evidence is that these creoles also show similarities to Krio, a creole spoken today in Sierra Leone (where it is the de facto national language) and other parts on the west coast of Africa (Wolfram and Schilling 2016). Over time, contacts with neighboring varieties led this creole to become more like other English varieties through a process called decreolization, where the creole-specific structures become lost and replaced by features that are non-creole. In the case of AAL, those features are English specific. It’s important to note that this process is gradual and incremental, as some of the remnants can be seen in modern AAL. Features such as copula absence (He is here –> He here), third person singular and possessive –s absence (Michael runs –> Michael run; The boy’s dog –> The boy dog), and the tense and aspect system, all lend credence to the Creole Hypothesis (Wolfram and Schilling 2016).

The video below, produced by the Language and Life Project and is an excerpt from the 2017 documentary Talking Black in America, Dr. Emory Campbell discusses being a Gullah native and the relationship between Gullah and Sierra Leone.

Music

Like American music, all of American music is comprised of a wide range of local and global articulations throughout history. Songs performed by enslaved African people interacted with European music and dance performances and gave rise to new forms of music such as Gospel, Jazz, Blues, R&B, Rock & Roll, which would eventually spawn Heavy Metal and Punk Rock. The short 1970s documentary, Black Music in America; from then till now, provides a synopsis of the wide range of American musical forms with African roots.

Today, the ‘Bo Diddley beat’ continues to infuse African Yoruba rhythms into pop hits. Bo Diddley was a blues and rock & roll musician in the 1960s who popularized a variation of the 3-2 clave rhythm, one of the most common bell patterns found in Afro-Cuban music that has been traced to sub-Saharan African music traditions. The beat is also similar to a rhythmic pattern known as “shave and a haircut, two bits”, that has been linked to Yoruba drumming from West Africa. Listen to the beat below; can you recognize it?

The video below is Bo Diddley introducing the beat to an American audience in 1955.

The Bo Diddley beat would go on to influence musical hits for several decades. Listen to the NPR tribute to Bo Diddley and learn about the history of the beat and the variety of songs influenced by it.

Dance

In addition to music, African dance styles have also shaped popular dance moves in the U.S. One example is ‘The Charleston,’ which is incidentally named after the city with the largest slave port in early American history. The Charleston was popularized in 1923 with the song The Charleston, composed by James P. Johnson, from the Broadway show Runnin’ Wild. The dance was most popular throughout the 1920’s among rebellious youth who danced by flapping arms and kicking up the heels, hence the term ‘flappers.” Yet, the origins of the dance can be traced back to the coast of Charleston and the community of people who live there and performed the “Juba,” a dance brought to Charleston by enslaved African Americans and performed by dock workers in the early 1900’s. The Juba involves rhythmic stomping, kicking, and slapping, and it became a challenge dance of the American American community at the time. By the turn of the twentieth century, The Charleston was well-known amongst African American communities. During World War I, many Southern African Americans migrated to northern states and brought the dance with them. In 1911, the Charleston was performed by the Whitman Sisters in their famous stage act and became part of Harlem stage productions in 1913. Nearly a decade later, the Charleston landed on Broadway in the all-black stage play, Liza. While the dance became popular amongst black musicians, it did not meet a white audience until the Broadway show Runnin’ Wild. The Charleston went on to influence 1950s swing dances and other popular dance challenges such as the “Mashed Potato.”

Watch the 1920s clip of a Euro-American couple dancing the Charleston.

The Juba dance also influenced the popularity of tap dance in the second half of the 20th century, and African dance moves were further popularized i in Jazz, R&B, and Rock and Roll movements.

African dances continue to influence dance culture in the U.S. today. Many contemporary American college students are familiar with a type of challenge dance called stepping which became popularized by African-American students at colleges and universities throughout the United States. The American film, Stomp the Yard, is a romantic drama that features step-dancing. Watch the trailer below to see examples of step dance.

Contemporary American Step Dance owes its origins to the Welly Gumboot Dance which originated in mines throughout southern Africa. African men laboring in European-owned mines were forbidden to congregate and sing, dance and play hand drums. As a result, the workers improvised by using their bodies, helmets and boots (British brand known as the ‘Welly’) as percussion instruments. The adapted dance spread throughout Africa, and in time, the African step dance migrated to the United States and blended with other performance moves such as gymnastics, break-dancing and hip hop. Watch the Gumboot Dance in the video below to identify similarities in the dance and step performances shown the the film, Stomp the Yard.

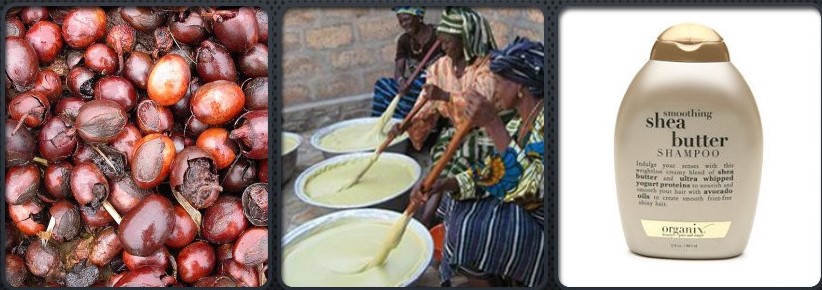

Cosmetics and Personal Care Products

A variety of cosmetics and personal care products popularized in the United States are of African origin, and are packaged and marketed in ways that are familiar to an American consumer base. Shea Butter comes from West Africa. The English word “shea” comes from s’í, the tree’s name in Bambara. It is known by many local names, such as kpakahili in the Dagbani language, taama in the Wali language, kuto in Twi, kaɗe or kaɗanya in Hausa, òkwùmá in the Igbo language, òrí in the Yoruba language, karité in the Wolof language of Senegal, and nkuto (Akan) or nku (Ga). The ivory-colored fat comes from the nut of a tree (Vitellaria paradoxa) , and it is used for medicinal, cooking, cosmetic, and industrial applications. It has a sun protection factor of six. In the U.S. it is a common ingredient in cosmetics as a moisturizer, salve or lotion.

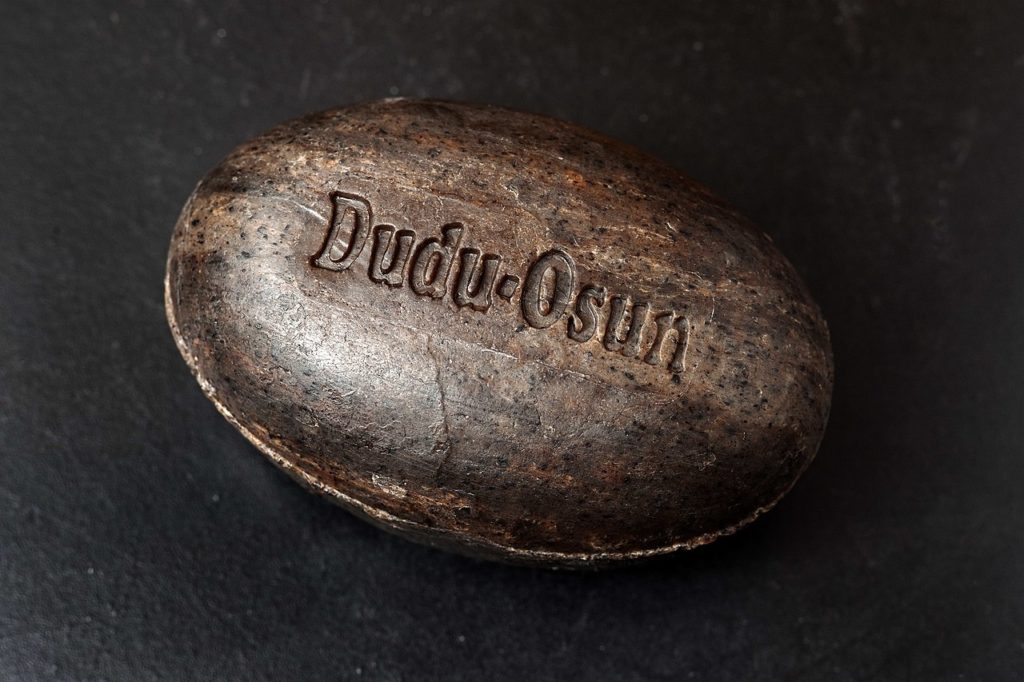

African black soap, or black soap (also known by various local names such as sabulun salo, ose dudu and ncha nkota) also originated in West Africa. It is made from the ash of plants and dried peels, which gives the soap its characteristic dark color. It has become a popular in North America due to its benefits on oily and acne-prone skin and some antimicrobial properties against skin microbiota such as Staphylococcus aureus, Escherichia coli and Candida albicans. In West Africa, especially Ghana, black soap is often made by women and exported throughout the world. A variety of black soap known as ose-dudu originated with the Yoruba people of Nigeria. Another variety of black soap known as ncha nkọta which roughly translates to “soap you can scoop” because of its soft texture originated with the Igbo people of Nigeria.

Religion

Mass enslavement of African people also included the conversion of enslaved people to Christianity. This reshaped the religious landscape in North America as a growing number of African congregants highlighted elements of Christian worship and scriptures that resonated with the beliefs and practices observed in Africa. Pentacostalism was among the first integrated denominations in early American Christianity, and contemporary practice includes elements of worship that resonate with African religious traditions. A ring shout is an ecstatic, transcendent religious ritual, first practiced by enslaved African people in the West Indies and the United States. Worshipers move in a circle while shuffling and stomping their feet and clapping their hands. The ring shout was Christianized and practiced in some African American churches into the 20th century, and it continues to the present among the Gullah people of the Sea Islands and in the Black Church. A contemporary form, known as a “shout” (or “praise break”), is practiced in many Black churches and non-Black Pentecostal churches to the present day.

William J. Seymor led the Azusa Street Revival in early American Petacostalism. In time, the first generation of African American leaders emerged from the revival movement. George Liele, Andrew Bryan and David George built the first black Baptist churches in Georgia and South Carolina during the height of the American Revolution. The black Baptist movement thrived in British-occupied Savannah and Charleston. After the war, the geographical reach of their combined ministries was remarkable. By 1790 George Liele had emigrated to Jamaica with the Loyalists, and he preached regularly to 350 converts. David George established seven churches in Nova Scotia before leaving for Sierra Leone, West Africa, where he founded another Baptist church. By 1800 Andrew Bryan’s First Baptist Church of Savannah had grown to a congregation of 700.

African religious elements also integrated with to create new religious movements. Hoodoo (Gullah Voodoo/Lowcountry Voodoo) is a blend of spiritual practices, traditions, and beliefs practiced by enslaved African people in North America. Worship took place in secret from slaveholders, and the mix of people from many different African cultures led to a new religion comprised of several beliefs and practices as well as medicinal uses of plants and animals. Hoodoo is also known as “Lowcountry Voodoo” in the Gullah South Carolina Lowcountry, and it spread throughout the U.S following the Great Migration of African-Americans out of the South after emancipation. Black theology.

Names

References and Resources

- Carlson, Amanda and Robin Poynor, eds. Africa in Florida: Five Hundred Years of African Presence in the Sunshine State. Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 2013. 528 pp.

- McWhorter, John. 2017. Talking Back, Talking Black: Truths about America’s Lingua Franca.

- New York: Bellevue Literary Press.

- Dodson, Howard. 2003. ‘America’s Cultural Roots Traced to Africa’ National Geographic February 5, 2003.

- Terrell, Dontaira. 2015. ‘The Untold Impact of African Culture on American Culture’ Atlanta Black Star June 3, 2015.

- Gross, Rebecca. 2014. The Influence of Africa on U.S. Culture. National Endowment for the Arts. Issue 2014 No 1.

- Ohio State University Department of Animal Science African Livestock Breeds.

- Kperogi, Farooq. 2.13. ‘The African Origin of Common English Words’ Nigeria Village Square (see original sources in article) July 27, 2013

- Holloway, Joseph E. Africanisms in American Culture. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2005. Internet resource.

- Roots of African American Music. Smithsonian Institute

- Tamlyn, Garry Neville (March 1998). The Big Beat: Origins and Development of Snare Backbeat and other Accompanimental Rhythms in Rock’n’Roll

- Vass, Winifred Kellersberger. The Bantu Speaking Heritage of the United States. University of California at Los Angeles. Center for AfroAmerican Studies. Monograph Series. No. 2.

- Shout Because You’re Free: The African American Ring Shout Tradition in Coastal Georgia. University of Georgia Press. 1 October 2013. pp. 168–170.

- Diouf, Sylviane. Servants of Allah: African Muslims Enslaved in the Americas. New York: New York University Press, 1998. ISBN 0-8147-1905-8

- Floyd Jr., Samuel A. “Ring Shout! Literary Studies, Historical Studies, and Black Music Inquiry.” Black Music Research Journal, Vol. 22 (2002): 49-70.

- Parrish Lydia. Slave Songs of the Georgia Islands. 1942. Reprint, Athens, Ga.: University of Georgia Press, 1992.

- Turner, Lorenzo Dow. Africanisms in the Gullah Dialect. 1949. Reprint, New York: Arno Press, 1969

- Paul Finkelman (6 April 2006). Encyclopedia of African American History, 1619-1895: From the Colonial Period to the Age of Frederick Douglass Three-volume Set. Oxford University Press, USA. pp. 363–364. ISBN978-0-19-516777-1.

For Discussion in Canvas: Africa in Florida

Find an example of an African cultural survival in Florida. Describe the social and historical context of the cultural survival and identify the ways it has adapted and changed over time. In what ways did it blend with other cultural forms from Europe, South America, indigenous or Asian influences to create a new form?

For Extra Credit: Visit the Africa in American Cuisine lesson and prepare an African or African-American meal.

When you complete the lesson, move on to Africa in Europe.