Lesson Objectives:

- identify diverse hierarchical and heterogeneous organizations within communities

- describe how marriage, family, and household are socially constructed concepts

- evaluate how ideas about marriage, family and household are dynamic and vary cross-culturally

- analyze internal diversity within a selected community

The anthropological perspective on marriage, family and households begin with the understanding of the heterogeneous and hierarchical nature of social systems within communities, households, and families. This is important because researchers oftentimes present communities, households and families as a homogeneous group by ignoring the internal power structures that characterize social relations within the social unit. Feminist scholars were among the first to interrogate the Myth of Community by unveiling how research studies that rely on ‘household surveys’ fail to account for the ways that each household member’s experience is shaped differently according the social positioning of each household member (Stacey 1969; Guilt and Kaul-Shah 1998; Spring 1973).

In their book, The Myth of Community (1998), Irene Guijt and Meera Kaul Shah examine the ways that rural women have been left out ofdevelopment programs and policy-making because policy-makers have approached ‘communities’ and ‘households’ as a uniform social unit comprised of individuals who think, act and experience the same way. Guilt and Kaul Shah argue that in fact, communities are highly heterogeneous and social hierarchies can be based on factors such as race, ethnicity, gender, education, lifestyle choices, sexual orientations, residence, occupation and livelihood, citizenship, etc. Similarly, households and families are also characterized by power structures which can be shaped by gender relations, age-based authority systems, marriage patterns, kinship structures and even individual personalities. In light of this, research studies and programs that fail to account for the social hierarchies that operate within a community, household and family will inevitably leave out members who are marginalized and powerless.

What is a household?

While the concept of a ‘household’ can be considered a standard residential unit in ethnographic research, the social composition within a household not only varies widely cross-culturally, households and household relationships can be quite different within the same social group. Previous anthropological research has generally relied on euro-centric nuclear-family models to define households in various cultural contexts (Schneider 2000). Yet, contemporary anthropologists are now beginning to recognize that a household is a dynamic unit because social organization within the household and household composition are constantly changing. Events such as marriage, birth, death, work migration, and death can dramatically alter household composition and social relations within a residential unit. In addition, some members may occupy more than one residential unit according to seasonal variations related to activities such as farming or employment. The dynamic nature of households can make it difficult, if not impossible, to rely on the ‘household’ as a unit of analysis in ethnographic research.

What is a family?

Like household, the concept of ‘family’ also varies cross-culturally. From an anthropological perspective, a family is a group of people who are related in some way (Kottak 2012). Early anthropological research defined family according to blood relations; this was based on a euro-centric perspective on family that emerged from aristrocratic inheritance patterns that privileged patrilineal (male-centered) biological kinship ties. More recent research on family and kinship has shown that the concept of ‘family’ and the social structure of kinship can vary cross-culturally. Matrilineal societies might structure kinship and family groups according to the female biological line while other social groups ignore biological relations and establish kinship and family relations as a system of close social ties that allow for ‘adoption’ into the kin system. In the United States, it is not unusual for some people to consider an animal, their ‘pet’, as a family member. From this perspective, kinship is about doing (action), not being (biology) (Dube 2000, Yanigisaki and Collier 2008, Hoffstaedler, Thomas and Busby 2008).

This makes ‘family’ and ‘kinship’ a social construct because the concepts are invented ideas that emerge from within a particular social system.

Marriage: obligation or choice?

Marriage is a social contract between people that can include legal, social, sexual, emotional, financial, and religious obligations. The structure of marriage contracts and relations vary cross-culturally. Some marriages are based on a contract between only two people, while plural marriages can include several. Polygamous marriages consist of a contract between one man and more than one woman, and polyandrous marriages consist of a contract between one woman and more than one man. Marriage contracts can also be part of a process aiming to maintain the social order of a group by forming durable alliances; a levirate marriage allows the brother of a deceased man to fulfill his brother’s marital obligations by marrying his brother’s widow, and a sororate marriage allows a women to fulfill the marriage contract of her deceased sister (Kottak 2012).

Within each culture, marriage contracts consist of a wide variety of social and economic expectations. Oftentimes, marriage expectations rest on the gender ideologies and expectations that are shared within the particular social group. Within the marriage, family, and household each individual can be expected to perform and carry out specific gendered roles and duties such as income generation, childcare, agricultural labor, taking out the trash, cooking, cleaning, etc. Like gender ideologies, marriage expectations are also dynamic because they adapt to changing circumstances.

Obligation

Marriage relations can be characterized by social duty and economic obligation. In early American society for example, marriage relations were often based on an economic arrangement between two individuals or between two families. The household was considered a productive unit and each individual carried out productive tasks and activities according to a gender and age-based division of labor. This is not uncommon in many societies today, particularly in agrarian (agricultural) societies, where production and survival play a central part of the social organization of the society. When marriage is considered an economic, or productive, contract, it is not unusual for marriage contracts to be arranged. In an arranged marriage, the marriage contract between people is coordinated by someone other than the parties who are engaged to enter into the contract. Marriages can be arranged by a matchmaker, an elder, or the parents of the individuals to be married and decision-making can be based on the best interest of the engaged parties, or the interest of the family of social group.

Choice

As the household economy shifts away from productive activities carried out in the home to income-generation outside of the home, the nature of marriage and family relations can change. This is because family and marriage relations are no longer bound to a division of household labor organized by gender and kinship, and in many cases, marriage and family relations are defined by desire and choice. In his book, The Transformation of Intimacy (1992), Anthony Giddens describes how industrialization and the transition from a productive to a consumptive society changed households and families because love, not the economy, became the central link in social relations. The film below describes the generational conflicts that emerge when children and parents hold conflicting ideas about the nature of marriage relations.

The drama, Arranged (2007) depicts the complicated process and contemporary conflicts associated with arranged marriages within Jewish and Palestinian cultures.

Social relations is post-industrial ‘consumer’ societies have been largely characterized as elective relationships based on individual desire and choice. In his book, Risk Society (1992), Ulrich Beck explains that ‘Western societies are experiencing ‘a surge of individuation’ in which globalized change is bringing to an end the contrasting influences of social class and gender as dominant forms of industrialized society.’ What he means is that people are no longer bond to the organizational constraints of gender and class expectations established by the social group. Social relations have become liberalized, or ‘set free’, according to individual freedoms, personal wants and needs. As a result, new forms of social relations and organizations have emerged. Beck also points out however, that while social freedom can offer an immense amount of personal satisfaction, it also carries significant risks. This is because, unlike obligatory social relations and expectations that are codifed by the social group, elective relationships are vague and lack moral precepts for behavior. Therefore, elective relationships demand a significant amount of negotiation and strategizing between individuals because rights, roles and responsibilities are less certain. This is central part if the difference in divorce rates between liberalized marriages and obligatory marriages; elective marriages have significantly higher divorce rates because romance is perceived as a necessary part of the marriage contract (Ingraham 2008). In obligatory marriages, individual desire does not take priority over social alliances within and between groups, maintaining security, and fulfilling obligations.

Love & Romance

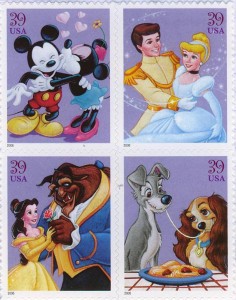

In liberalized societies, love and romance are often considered the foundation for elective marriage relationships. Critics argue that love-based marriages are unsustainable because passion usually wanes and ideas about love are usually idealized and unrealistic. Disney movies are often blamed for socializing America children to have unrealistic expectations for romantic relationships. Virtually every Disney movie includes a subplot revolving a romance-based relationship between humans (Cinderella), animals (Lady and the Tramp), inanimate objects (Cars), and even between humans and animals (Beauty and the Beast).

In liberalized societies, love and romance are often considered the foundation for elective marriage relationships. Critics argue that love-based marriages are unsustainable because passion usually wanes and ideas about love are usually idealized and unrealistic. Disney movies are often blamed for socializing America children to have unrealistic expectations for romantic relationships. Virtually every Disney movie includes a subplot revolving a romance-based relationship between humans (Cinderella), animals (Lady and the Tramp), inanimate objects (Cars), and even between humans and animals (Beauty and the Beast).

A salient aspect about romance models represented by Disney and other media outlets is that they usually revolve around one male human, animal or inanimate object and one female human, animal or inanimate object. This reflects euro-centric cultural ideas about the meaning of love and marriage. As contemporary societies become increasingly liberalized, static models for love and marriage are being challenged by a multiplicity of new forms of elective social arrangement. The tension between earlier models for obligatory marriage social contracts within a productive (including reproductive) unit and emerging models for marriage social contracts based on love and elective relationships has become a controversial debate in contemporary society. Marriage was a key aspect in the presidential and vice-presidential debates in 2008. Consider the similarities and differences between the perspectives on marriage expressed by Biden and Palin:

Both Palin and Biden recognized elective relationships between same-sex couples as significant and they agreed that same-sex couples should be entitled to certain rights such as hospital visitation and inheritance. Yet, both limited their definition of marriage as being a social contract exclusively between one man and one woman. This model is loosely based on obligatory marriage models rooted in marriage contracts in productive household units. Compare Biden and Palin’s ideas about marriage with the model set forth by James Neiley, a teenager living in Vermont: Bilerco.com Unlike Biden and Palin, Neely’s ideas about marriage reflect patterns emerging in liberalized societies where love, not the economy is the foundation for social relationships including marriage and family relations.

By examining the cross-cultural variations regarding marriage, family and household, it becomes clear that all three institutions are social constructs based on conceptual differences between the symbolic meanings of ‘marriage’, ‘family’ and ‘household’ as either an ‘institution’ or a negotiated relationship. These conceptual differences shape the ways that people interact with one another when they engage in social relations within marriage, family and household. In the next module, we will examine the ways that symbolic meanings associated with race and ethnicity shape social relations and the social organization of societies.

Readings: Budgeon and Roseneil. 2004. Beyond the Conventional Family. Current Sociology. V. 52 (2)

Your Score:

Your Ranking:

Discussion

Now is the time to select a community for your final project. How is your selected community heterogeneous and hierarchical? What demographic factors (race, class, gender, sex, age, nationality, etc) contribute to the social organization of the community? How are marriage and family relations organized and what are their symbolic meanings? Consider the ways that globalization and development have changed the social classifications for people in your selected community. In your responses to student posts, compare and contrast your community with the community they selected . Be sure to cite academic references for your data.

When you complete the discussion, move on to the Race & Ethnicity lesson.