Lesson Objectives:

- identify defining dimensions of culture

- recognize adaptive role of culture in human history

- examine relationship between culture and power

- analyze cultural artifact using terms and concepts from lesson

The anthropological approach to cultural diversity begins with the question, ‘What is Culture?’ One of the most widely quoted definitions of culture originated from early anthropologist, Edward Tylor (1871/1958):

‘Culture … is that complex whole which includes knowledge, belief, art, morals, law, custom, and any other capabilities acquired by man as a member of society.’ (1871/1958:1)

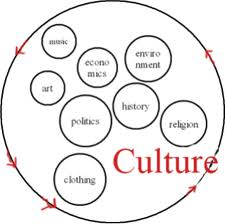

Building on Tylor’s definition of culture, contemporary anthropologists approach culture as a complex whole, or system, comprised of tangible artifacts (such as art and clothing) as well as intangible cultural artifacts (such as knowledge, language and beliefs). Culture is a system because it cannot be understood as a collection of separate parts; culture is a whole system of interconnected and interrelated phenomena. What this means is that human phenomena such as economics, religion, law, marriage, or gender cannot be considered distinctly separate spheres of human activity; they are interconnected and interrelated. In order to develop a better understanding of culture as a system, anthropologists must take a holistic approach to understanding culture by taking every cultural component into consideration.

Building on Tylor’s definition of culture, contemporary anthropologists approach culture as a complex whole, or system, comprised of tangible artifacts (such as art and clothing) as well as intangible cultural artifacts (such as knowledge, language and beliefs). Culture is a system because it cannot be understood as a collection of separate parts; culture is a whole system of interconnected and interrelated phenomena. What this means is that human phenomena such as economics, religion, law, marriage, or gender cannot be considered distinctly separate spheres of human activity; they are interconnected and interrelated. In order to develop a better understanding of culture as a system, anthropologists must take a holistic approach to understanding culture by taking every cultural component into consideration.

Nearly a century later, contemporary anthropologist Clifford Geertz portrayed culture as system of interconnected elements in his book, The Interpretation of Cultures (1973) He states that culture is:

“a system of inherited conceptions expressed in symbolic forms by means of which men communicate, perpetuate, and develop their knowledge about and attitudes toward life” (1973:89).

Geertz sheds light on the ways that humans create symbols of meaning that operate as an interpretative framework to view the world. Shared symbols and meanings offer a foundation for mutual perspectives and understandings. The goals of anthropological research, according to Geertz, is to understand culture by interpreting shared meanings that are expressed in symbolic ways. We will explore Geertz’s theoretical framework in greater detail when we address Language in the next section, Religion in the fourth module, and Structuralism toward the end of the semester. For now, we will focus on a defining feature of culture that lends to a greater understanding of diversity; the notion that culture is acquired through learning and sharing.

Culture is Learned

People are not born with culture; culture is acquired by learning and sharing with others. The process of learning, or acquiring, culture is called enculturation. Enculturation can take place both implicitly or explicitly. Explicit enculturation occurs when culture is clearly expressed. During a church sermon, for example, a congregation explicitly learns the cultural beliefs and practices of their specific religious community when the norms and values are stated directly. Implicit enculturation occurs when culture is learned through indirect expression. When a female toddler walks into a room wearing pigtails and a frilly dress, for example, her adult role models might smile and exclaim ‘look at how cute you are!’ By interpreting the adults’ response, she implicitly learns that within her cultural group it is appropriate for her to look and dress in a specific way. Her brother, however, might elicit a very different response for the very same behavior which thereby signals to him it is considered inappropriate to look and dress a specific way. Through constant interaction, children implicitly and explicitly learn cultural norms and values. As people move and interact with one another, they are consistently experiencing enculturation and participating in the enculturation of others, both implicitly and explicitly, to tangible and intangible culture. This is what makes culture shared.

Culture is Shared

Culture is learned because culture is shared. The sharing of culture requires contact and communication between individuals, and shared culture connects people to one another. This makes culture centrally important in social relationships which are the building blocks of a society. Mutual understanding through shared culture facilitates social cohesion and group formation. Because of this, culture is not only a vehicle for social inclusion, it can also contribute to social exclusion because culture also embedded within social systems of power.

Culture and Power

The idea of cultural hegemony was proposed by Italian philosopher, Antonio Gramsci, when he produced The Prison Notebooks during his incarceration by Benito Moussolini in 1926. In his writings, Gramsci described how those in power are able to maintain social power by manipulating and enforcing specific norms and values in a society. In essence, the culture of those who are in power becomes the culture of those who are oppressed. Hegemonies become embedded in society because they are often learned implicitly and during childhood before the individual has developed critical thinking to contest learned ideas. As a result, hegemonies are often unapparent and this makes it difficult to recognize and challenge hegemonic culture. Watch this video for a 10-minute primer on hegemony.

Cultural hegemonies are powerful because culture is integrated in the daily lives of people, and culture shapes the way people view the world and themselves. This makes hegemony a useful tool to control and oppress people and justify social inequalities. Throughout India and the Middle East, for example, commercial advertisements for ‘Fair & Lovely’ skin-lightening cream are televised several times a day throughout programs that are primarily targeted to women and girls. Watch the television advertisement below and consider the implicit and explicit associations between skin color and specific social experiences.

To watch a different ‘Fair & Lovely’ commercial in English, click here.

Hegemony & Ethnocentrism

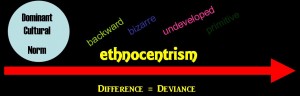

Hegemonies originate from the ethnocentric ideas of those who are in power. Ethnocentrism us the emotional tendency to place one’s own culture, values and ideas at the center, or as the ‘norm’, and to evaluate other cultures, ideas, and values according to how much they deviate from the ethnocentric norm.

Ethnocentric approaches to culture are often based on archaic evolutionary models that produce hierarchical orders based on a linear standard by which all cultures are measured and assessed. Ethnocentrism does not account for the unique experiences and cultural systems that emerge from different social and historical circumstances. More importantly, ethnocentrism undermines the significance of cultural diversity for human survival.

Why is Cultural Diversity important?

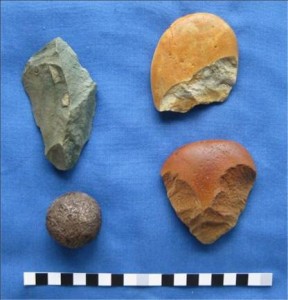

Culture is a defining feature of the human experience, and cultural diversity is a central factor for human survival in diverse environments. The human capacity for culture extends 2.5 million years as evidenced by stone tools and cave paintings. Archaeological evidence of culture originates in the Hominidae family that includes fossil and living humans, as well as chimpanzees and gorillas (Kottak 2012). Early research by primatologists such as Jane Goodall and Dian Fossey established that non-human primates engage in very similar behaviors as humans. Many primates live in societies with sophisticated social alliances. They can learn from experience and modify their behavior, fashion tools, solve problems, form hunting strategies, and some primatologists argue that non-human primates can learn language.

Culture is a defining feature of the human experience, and cultural diversity is a central factor for human survival in diverse environments. The human capacity for culture extends 2.5 million years as evidenced by stone tools and cave paintings. Archaeological evidence of culture originates in the Hominidae family that includes fossil and living humans, as well as chimpanzees and gorillas (Kottak 2012). Early research by primatologists such as Jane Goodall and Dian Fossey established that non-human primates engage in very similar behaviors as humans. Many primates live in societies with sophisticated social alliances. They can learn from experience and modify their behavior, fashion tools, solve problems, form hunting strategies, and some primatologists argue that non-human primates can learn language.

In her book, In the Shadow of Man (1971), Jane Goodall revealed very human-like behaviors of chimpanzees such as mothering, mourning, bullying, and building social alliances. Later primatologists have suggested that primates also engage in human-like behaviors such as lying, swearing and joking.

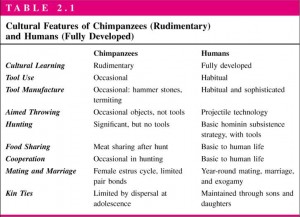

As primatologists continue to generate research that expands our knowledge about primate behavior, the differences between human and non-human primates seem to dwindle. For the time being, researchers agree that there are fundamental differences between humans and our primate relatives such as; more sophisticated cooperation and sharing (ie charities), mating throughout the year, exogamy (marriage outside of the social group), non-biological kinship systems, and the use of symbols as meanings.

Cultural Features of Chimpanzees (Rudimentary) and Humans (Fully Developed)

Culture as Adaptation

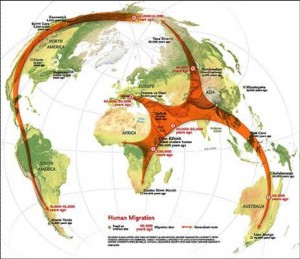

Despite the differences between human and non-human behaviors, anthropologists agree that all human populations have the capacity for culture. Research has shown that not only do all human populations have an equivalent capacity for culture, but culture has been key to the survival and success of humans as a species (Kottak 2012). Through cultural diversity, humans have been able to adapt, and thrive, in a wide range of diverse environments.

“It is not the strongest of the species that survives, nor the most intelligent that survives. It is the one that is the most adaptable to change.”– paraphrase of Darwin in the writings of Leon C. Megginson (1987)

Adaptation is the way people cope with environmental forces and stress. Different environmental forces and stressors lead to different forms of adaptation. Humans are among the most adaptable species on the planet, and the human capacity for a wide range of diverse adaptations has enabled the species to survive in virtually every ecological niche; from tropical islands to the Arctic ice caps and from the deep sea to outer space.

Adaptation is the way people cope with environmental forces and stress. Different environmental forces and stressors lead to different forms of adaptation. Humans are among the most adaptable species on the planet, and the human capacity for a wide range of diverse adaptations has enabled the species to survive in virtually every ecological niche; from tropical islands to the Arctic ice caps and from the deep sea to outer space.

Human adaptation occurs in both biological and cultural ways. Biological adaptation includes genetic adaptation, long-term physiological or developmental adaptation, and short-term physiological adaptation. a large body of research in biological anthropology explore the many ways in which the human species has biologically adapted to different environments. This course will focus on cultural adaptation.

Cultural adaption is both social and technological. Adaptive technology ranges from stone tools to medicine, electricity and digital media. Social adaptation refers to changes in human behavior. While early anthropologists focused on ‘Social Darwinian’ approaches to human adaptation by focusing on individual ‘fitness’ and explaining human survival according to the ideas set forth by Charles Darwin, such as ‘natural selection’ and ‘survival of the fittest’, contemporary anthropologists are now beginning to recognize how culture and social bonds enhance human’s ability to survive in adverse circumstances. This approach draws from the ideas of Russian evolutionary biologist, Peter Kropotkin, who argued that cooperation, not competition, was the key to survival. In his book, Mutual Aid: a factor of evolution (1902 ), Peter Kropotkin described how many species, including humans, rely on social networks to survive as a group:

‘In the animal world we have seen that the vast majority of species live in societies, and that they find in association the best arms for the struggle for life: understood, of course, in its wide Darwinian sense — not as a struggle for the sheer means of existence, but as a struggle against all natural conditions unfavourable to the species … The unsociable species, on the contrary, are doomed to decay.’

Culture is Dynamic

Since culture is learned, shared and adaptive to changing circumstances, it is dynamic. This means that culture is constantly changing as people encounter novel circumstances and new interactions. In addition, different people within the same cultural group interpret and perform culture in different ways according to their unique experiences and positioning within a particular society. The dynamic nature of culture challenges ideas about ‘traditional’ or ‘authentic’ culture which represents culture as static and independent of changing circumstances or individual agency.

The animation below explains the cultural shift from using ‘trees’ as a metaphorical symbol to organize reality to the use of ‘networks’. Consider the ways that this cultural shift reflects new ways of thinking about reality as humans experience changing circumstances such digital environments and ideas about equality.

In this animated lecture, Manuel Lima describes how the sciences shifted from a field that interpreted reality according to hierarchical orders organized symbolically with ‘trees’ to non-hierarchical systems organized symbolically by ‘networks’. Disciplines in the social sciences, such as anthropology, also underwent this shift from organizing cultural groups according to an evolutionary hierarchical order to interpreting cultures as networked systems.

Readings: Parenti, Michael. 1999. ‘Reflections on the Politics of Culture‘ in Monthly Review Volume 50 Issue 9 (February)

So what did you learn?

Before you complete the discussion below, take this quiz to test your knowledge of a few terms and concepts introduced in this lesson.

Your Score:

Your Ranking:

Discussion: Using what you have learned about Culture in this section and in the Parenti reading, analyze the ‘Fair & Lovely’ commercial advertisement posted above. Answer the questions: Imagine that you are an eight year old girl watching television in a small village in Southern India and Fair & Lovely commercials air several times during the program you are watching. What cultural ideas and values are implicitly or explicitly expressed by these commercials? Whose values are they and where did they come from? What type of conclusions would you draw based on your observation of this commercial? How can these hegemonic ideas be used to justify social inequality? Can you think of hegemonic ideas, norms and values that are pervasive within your own culture? Do you agree or disagree with Michael Parenti about power and the politics of culture? Explain why. Be sure to use terms and concepts from the lesson (in italics and bold) in your post, and respond to another student’s post to receive credit.

When you complete the discussion, move on to the Language & Culture lesson.